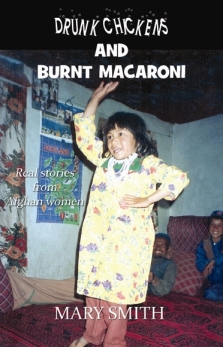

AWARD-winning writer, Mary Smith, can turn her pen to just about any style of writing. She is a journalist, features writer and novelist with immense talent and it’s no surprise that her yearly events schedule is hectically-packed with tours, commissions, projects and interviews by the press. Mary’s spell abroad in Afghanistan showed her a very different side of life there to what the world’s media has recently portrayed. Her books No More Mulberries and, more recently, Drunk Chickens and Burnt Macaroni expose a gentle, human side of this troubled country before the rise of the Taliban.

AWARD-winning writer, Mary Smith, can turn her pen to just about any style of writing. She is a journalist, features writer and novelist with immense talent and it’s no surprise that her yearly events schedule is hectically-packed with tours, commissions, projects and interviews by the press. Mary’s spell abroad in Afghanistan showed her a very different side of life there to what the world’s media has recently portrayed. Her books No More Mulberries and, more recently, Drunk Chickens and Burnt Macaroni expose a gentle, human side of this troubled country before the rise of the Taliban.

Features, journalism, novels and poetry are all variations of fact and fiction that each requires very different styles. How difficult is it to turn your approach to writing on and off in any given project?

Well, if I’ve had articles to write to a deadline I find it difficult to switch immediately to writing poetry or fiction. I need a bit of head space in between the different types and styles. I might clean the house, though that makes me bad-tempered, or I might do some research for a project. It is easier the other way round. If I’m working on fiction or poetry and am commissioned to write a magazine feature, which has a deadline, then I can go straight into the journalism.

How would you describe your individual style when writing fiction?

Goodness, you ask difficult questions, Sara. I guess I would say my fiction style is engaging and accessible. Someone once told me he’d picked up No More Mulberries, not sure if it was his kind of thing, and said he found he ‘just slipped right into it.’

To what extent has your time in Pakistan and Afghanistan influenced you as a writer?

I spent ten years working in Pakistan and Afghanistan with a small health organisation and that time has been hugely influential on me as a writer in so many ways. While I was working in Afghanistan I began writing articles which were regularly published in The Guardian Weekly and the Herald Saturday magazine. I wrote because I wanted to share my experiences and my discoveries and understanding with people back home who would not have the opportunity to live in those countries. There is something about Afghanistan which gets under the skin and never leaves and it has certainly informed much of my writing – both poetry and prose.

I spent ten years working in Pakistan and Afghanistan with a small health organisation and that time has been hugely influential on me as a writer in so many ways. While I was working in Afghanistan I began writing articles which were regularly published in The Guardian Weekly and the Herald Saturday magazine. I wrote because I wanted to share my experiences and my discoveries and understanding with people back home who would not have the opportunity to live in those countries. There is something about Afghanistan which gets under the skin and never leaves and it has certainly informed much of my writing – both poetry and prose.

Would you advise fledgling authors to take a course in creative writing?

- I think some creative writing courses are extremely useful for fledging authors. I took a creative writing module at university which was excellent and pushed me in new writing directions. I would never have written poetry if I hadn’t taken the course – or monologues. I discovered I enjoyed writing monologues, something I developed further when Cally Phillips was dramatist-in-residence in Dumfries and Galloway. Spending time with a group of writers is also of benefit. I do think, though, people should be very clear about what writing courses can and can’t do. When universities promote their MLitt courses they highlight the names of the handful of ex-students who have ‘made it’ since taking the course – they do not mention the hundreds of students who never get published. If someone wants to take a course to hone the craft of writing, learn about and try different genres, enjoy the buzz of being with like-minded peers then I’d say go for it. If someone thinks signing up for a Masters in Creative Writing means publication is just around the corner I’d encourage them to think again.

You obviously have a deep knowledge of life in a troubled country. Was it difficult for you to find a literary slant in your novel No More Mulberries and narrative non-fiction Drunk Chicken and Burnt Macaroni?

- It took a wee while to find my voice. I started by writing non-fiction, wanting to introduce readers to the people of Afghanistan but when it was being returned by publishers and agents they all said there wasn’t enough of ‘me’ in it. I didn’t want the book to be about me – it was to be about Afghan women and their families – and didn’t really understand I wasn’t being told to write about my role in Afghanistan but to find a way to let readers feel they were on the same journey as the narrator. I was writing as an objective reporter rather than as someone very much involved in the lives of the people about whom I was writing.

What message are you trying to convey to your readers in your works?

In both the novel No More Mulberries and the non-fiction Drunk Chickens and Burnt Macaroni: Real Stories of Afghan Women I am trying to provide readers with a different view of life in Afghanistan, especially for women, than the one portrayed by the media. We are told – on television, in newspapers and in many novels – Afghanistan is one of the worst countries in the world to be a girl because of the lack of education; enforced marriage at a very young age – and given the impression Afghan husbands are brutal wife beaters. I am not trying to say life is just fine for Afghan women. It’s tough – there are husbands who beat their wives, just as there are here – a lack of health resources mean a very high infant mortality rate, working in the fields is hard, hard work but it isn’t right to give such a one-sided picture. My friend’s daughter won a scholarship to study in India where she graduated with a degree in electrical engineering and, back in Kabul, now works for the leading telecommunications company in the country – and is about to embark on a Masters programme. She has not been married off. Her father was not some rich warlord but worked as a driver then an office administrator. In the novel I also try to show the men, too, especially those who want to be more liberal have a huge weight of cultural baggage to shed. Dr Iqbal was ostracised as a child because he had leprosy. Returning to his village as a doctor with a foreign wife gives him status again but his behaviour and attitudes are constantly under scrutiny by the villagers to ensure he doesn’t step out of line. Could be anywhere in rural Scotland, really – except for the leprosy!

In both the novel No More Mulberries and the non-fiction Drunk Chickens and Burnt Macaroni: Real Stories of Afghan Women I am trying to provide readers with a different view of life in Afghanistan, especially for women, than the one portrayed by the media. We are told – on television, in newspapers and in many novels – Afghanistan is one of the worst countries in the world to be a girl because of the lack of education; enforced marriage at a very young age – and given the impression Afghan husbands are brutal wife beaters. I am not trying to say life is just fine for Afghan women. It’s tough – there are husbands who beat their wives, just as there are here – a lack of health resources mean a very high infant mortality rate, working in the fields is hard, hard work but it isn’t right to give such a one-sided picture. My friend’s daughter won a scholarship to study in India where she graduated with a degree in electrical engineering and, back in Kabul, now works for the leading telecommunications company in the country – and is about to embark on a Masters programme. She has not been married off. Her father was not some rich warlord but worked as a driver then an office administrator. In the novel I also try to show the men, too, especially those who want to be more liberal have a huge weight of cultural baggage to shed. Dr Iqbal was ostracised as a child because he had leprosy. Returning to his village as a doctor with a foreign wife gives him status again but his behaviour and attitudes are constantly under scrutiny by the villagers to ensure he doesn’t step out of line. Could be anywhere in rural Scotland, really – except for the leprosy!

Does poetry help to hone your skills as a writer?

- Well, you may not think so when reading the answers to your questions but writing poetry does lead to writing with greater precision and conciseness – both skills required in journalism.

What other subjects interest you enough to write a book about them?

- I’d quite like to write a book tracing the parallel lives of two women born on the same day – one in rural Scotland and one in Afghanistan. Obviously the circumstances of their lives would be very different but I’m interested in highlighting the similarities in their outlook on life.

Do you have a work in progress at the moment?

- My current project is a biography of a woman who became an engineer in the 1920s and was Scotland’s only car manufacturer. She was a real pioneer in many ways – taking part in trial driving and competing against men, establishing a hugely successful laundry business – yet few people have heard of her today so I’d like to tell her remarkable story.

For more information on Mary check out:

Her website: http://www.marysmith.co.uk

Buy her books on Amazon: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Mary-Smith/e/B001KCD4P0

Another great interview, ladies. I love the way you’ve used your own experience to give those Afghan women a voice, Mary. Your new ideas sound fascinating too!

Thanks, Rosemary. The woman engineer/car manafacturer was a fascinating person and I hope others will enjoy her story – when I finally get it written.

Another interesting interview – thanks both. I like the sound of the parallel lives novel.

You focus a lot on women’s lives, which I like a lot. The new car manufacturer book is going to be interesting! And I love your poetry!

[…] including poetry, fiction, memoir and history from Sally Hinchcliffe, Donald Adamson, Hugh Bryden, Mary Smith, D D Hall, Gwen Kirkwood, Margaret Elphinstone, Claire Cogbill, JoAnne McKay, Sara Bain, Kriss […]